Quick Links

On Linux, you install software from package management applications like the Ubuntu Software Center. But not every piece of software is available in your Linux distribution’s software repositories.

You should only install software from sources you trust, just like on Windows. Much of this advice also applies to other Linux distributions, so we’ll note what’s Ubuntu-specific and what’s Linux-in-general.

DEB Package Files

Ubuntu software packages are in .deb file format. This includes packages you download from the Ubuntu Software Center and with apt-get -- they’re all .deb files.

However, you can also install .deb packages from outside of Ubuntu’s software repositories. Many companies that produce software for Linux offer it in .deb format. For example, you can download .deb files for Google Chrome, Google Earth, Steam for Linux, Opera, and even Skype, from their official websites. Double-click the file and it will open in the Ubuntu Software Center, where you can install it.

Ubuntu is based on Debian, which created the .deb package format. Other Linux distributions will have their own package format if they’re not based on Debian. For example, Fedora and other Red Hat-based distributions use .rpm packages. Many companies that offer software for Linux offer it in a variety of package formats for different distributions.

Third-Party Package Repositories

Ubuntu runs its own package repositories full of open-source (and some closed-source) software compiled and packaged for Ubuntu. However, anyone can set up their own package repositories.

Third-party package repositories are often added to your system seamlessly. For example, when you install Google Chrome or Steam from a .deb file, the .deb file adds the official Google or Valve software repository to your system. When the package is updated in the repository, you’ll be notified of updates and can install them via the Software Updater application. Unlike on Windows, updates for all your installed software can be managed in one place.

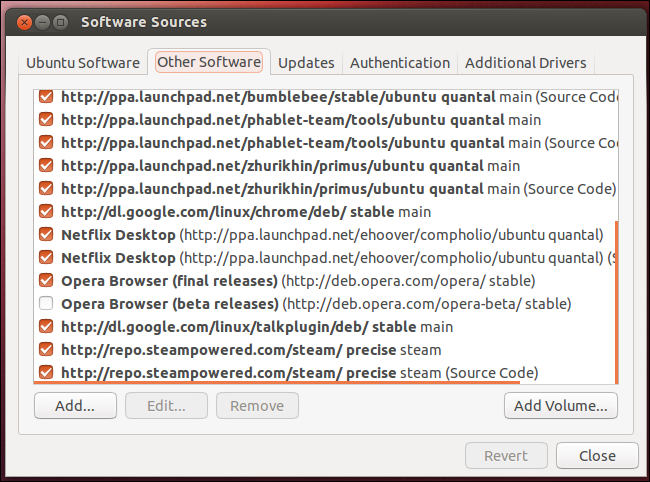

You can view your software repositories and add more (if you know their details) from the Software Sources application included with Ubuntu.

Other Linux distributions also support third-party repositories, but repositories and the software they contain are distribution-specific.

Personal Package Archives (PPAs)

PPAs are another form of third-party package repositories. They’re hosted on Canonical’s Launchpad system, where anyone can create a PPA.

PPAs often contain experimental software that hasn’t been officially added to Ubuntu’s main, stable repositories. They may also contain newer versions of software that aren’t yet considered stable enough to make it to Ubuntu’s main repositories.

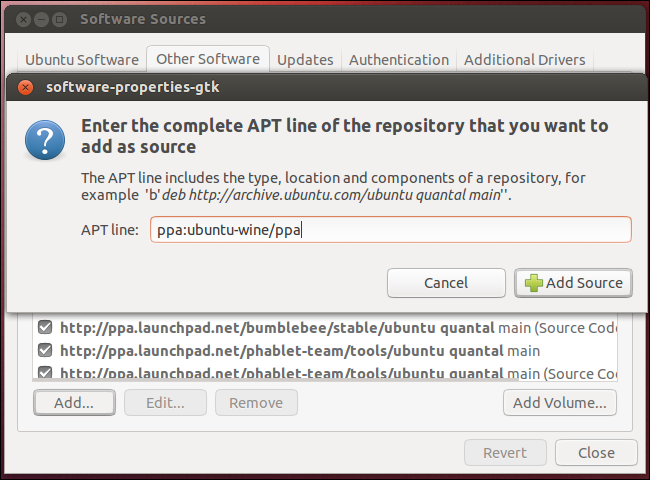

For example, Ubuntu’s Wine Team offers a PPA with the latest releases of the Wine software for running Windows applications on Linux. To add it, you would add the following line to the Software Sources application above:

ppa:ubuntu-wine/ppa

Each PPA page on Canonical’s Launchpad website includes instructions for adding the PPA to your system. Once a PPA is added to your system, you can install packages from the PPA using standard software like the Ubuntu Software Center, Software Updater, and apt-get command-line tool.

Compiling From Source

All binary software is compiled from source code. Ubuntu’s .deb packages contain software compiled specifically for the release of Ubuntu you’re using. These applications are compiled to use the software libraries available for your Ubuntu release.

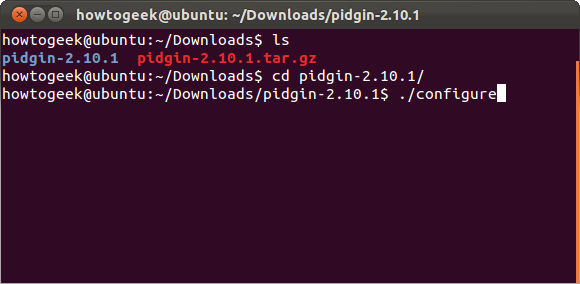

The developers of a particular piece of software generally release the software in source code form. Linux distributions take the source code, compile it, and create packages for you. However, you can also download a program’s source code and compile it yourself. You shouldn’t normally need to do this on Ubuntu. Most experimental software you might want is probably in a PPA, where someone’s already done the hard work for you.

On other distributions, it may occasionally be necessary to compile a program to get the latest version you need or install a program that isn’t available in your repositories. However, the average Linux user -- and even many geeky Linux users -- will never have to compile something from source.

Source code files are generally distributed in .tar.gz format, but that’s just a type of archive -- .tar.gz files could contain anything, just like .zip files can.

Binary Programs

Some programs are distributed in binary form, not source code form. This may be because the program is closed-source and the program’s distributer doesn’t want to do the hard work of packaging it for various distributions.

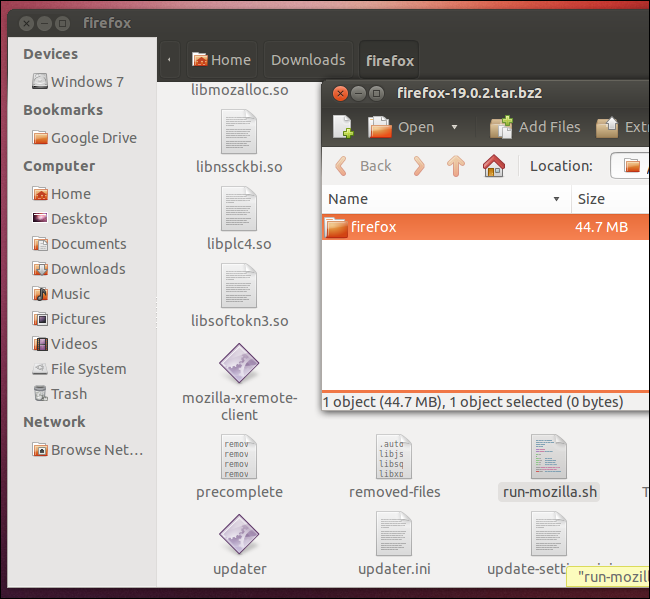

For example, Mozilla offers Linux downloads of Firefox binaries in .tar.bz2 format. (.tar.bz2 is just another archive format, like a zip file.) You can download this archive, extract it to a folder on your computer, and run the run-mozilla.sh script inside it (just double-click it) to run the downloaded Firefox binary.

However, you shouldn’t do this in the case of Firefox. Use the Firefox package that comes with your operating system -- it’s probably better optimized, faster, and will update through your standard package management tools. Still, if you’re using an older distribution of Linux that comes with an outdated Firefox, you can download the Firefox binary to your computer and run it from a directory without needing any system-wide permissions to install it.

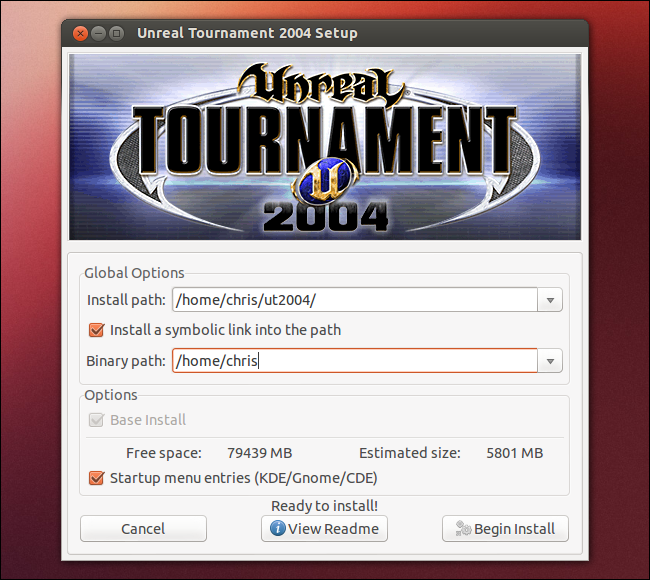

Much closed-source software (particularly older, unsupported closed-source software) is distributed in unpackaged binary form. Software like the Linux ports of Doom 3, Quake 4, Unreal Tournament 2004, and Neverwinter Nights are distributed in binary packages and even have Windows-like installers. These installers are actually just programs that extract the game’s files to a folder and create application menu shortcuts.

Of course, there are other ways to install software on Ubuntu. The Zero Install (also known as 0install) project has been trying to change Linux software installation for over five years, creating a system for installing desktop software that works across all Linux distributions. However, the Zero Install project hasn’t gained much traction. Most Linux users are well-served by their Linux distribution’s package manager -- particularly if they’re using Ubuntu, which most software is packaged for.